We Want No Caesars: Reflecting on Nehru's 1937 Rashtrapati Essay

An experiment in introspective leadership and uncovering of the human proclivity to crave power.

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either -- but right through every human heart -- and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–19561

The tenor of this Substack tends to refrain from political discourse. The frayed, partisan nature of Western politics leaves little room for meaningful dialogue about current issues.

However, after watching a selection of clips from the most recent presidential debate and observing the subsequent firestorm that has followed, the gag order levied upon political analysis in the Mimetic Journal will be momentarily lifted.2

In watching the two elderly men on stage squabble incoherently about their golf handicaps it does not take a keen political observer to acknowledge we are a long way from the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858.3

And while the modern debate format is a lamentable development, the protruding hubris oozing from both candidates is an even more regrettable affair.

Biden and Trump exude, albeit in different forms, an inordinate amount of pride. It is most on display when either candidate is asked a direct question about a prior mistake or policy blunder.

Rather than taking a path of humility, admitting their error, and accepting responsibility, their default involves launching ad hominem attacks upon each other, deflecting blame with cleverly devised red herrings, or boasting about personal accomplishments irrelevant to the topic at hand.4

At its root, both candidates have an exceeding thirst for power and little hunger for honest self-reflection.

The past few weeks have made this abundantly clear for President Biden as he refuses to admit his mental deterioration is problematic. He would rather hold on to the last crumbs of power and quite literally die in office as opposed to ceding any inkling of control to a younger candidate.5

The same applies for Trump in his refusal to accept the outcome of the 2020 election, ongoing legal troubles, and his unyielding desire to be in the Whitehouse despite being a 77-year-old billionaire with ample opportunity to enjoy retirement.6

There seems to be little to no internal, self-reflective dialogue taking place in either candidate’s mind.

While there is little hesitancy to point a finger calling each other a fascist or a socialist, neither man cares to stop and ask himself ‘If my will to power was left unabated, might I become one of the dirty political words that I so often accuse others of being?’

Introspection of this caliber is non-existent in modern politics, especially among Biden and Trump.

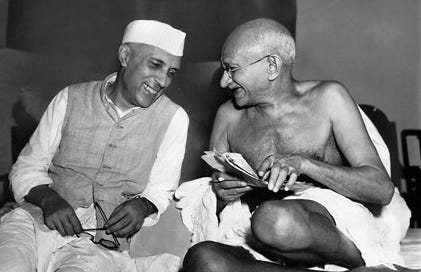

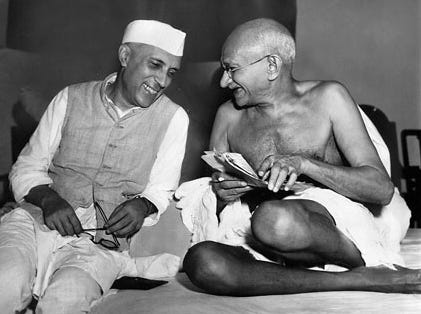

Enter Jawaharlal Nehru’s 1937 anonymous Rashtrapati7 essay published in the Modern Review.8 This little-known essay penned using the pseudonym Chanakya9 acts as a master class in introspection and self-understanding for world leaders.

At the time of writing the piece, no one suspected Nehru of being its author because of the damage it caused to his public image. The essay scathingly examines the potential psychological shifts that hypothetically could happen to Nehru if his power was left unchecked.

Chanakya asserts such a well-crafted, malevolent rebuke, that at its publishing many thought the essay was submitted by an ex-lover or political adversary using the name Chanakya to keep anonymity. The irony that Nehru himself offered up such a vulnerable self-criticism can hardly be missed.

To add clarity and avoid confusion it is important to note that in quoting the essay I will refer to the author as Nehru, even though at the time readers would not have known it was Nehru. It was not revealed to the public until 10 years after its publication that the pen name Chanakya was actually Nehru and that the Rashtrapati essay was merely an exercise in reflection.

Nehru starts by questioning whether or not his will to power is tainted. Nehru poses the following questions:

Is, all this natural or the carefully thought cut trickery of the public man? Perhaps it is both and long habit has become second nature now. The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be least of posing, and Jawaharlal has learnt well to act without the paint and powder of the actor. With his seeming carelessness and insouciance, he performs on the public stage with consummate artistry. Whither is this going to lead him and the country? What is he aiming at with all his apparent want of aim? What lies behind that mask of his, what desires, what will to power, what insatiate longings?10

Modern politicians are utterly unable to ask questions with the candor aforementioned. Nehru is keenly aware that despite his popularity and favorable public persona, inklings of unsatisfied longings for power still creep into his inner consciousness.

Nehru presses this question by first describing the boon his will to power has brought to India while continuing to question his intentions behind such acts. Nehru dissecting himself notes:

With an energy that is astonishing at his age, he has rushed about across this vast land of India, and everywhere he has received the most extraordinary of popular welcomes. From the far north to Cape Comorin he has gone like some triumphant Caesar passing by, leaving a trail of glory and a legend behind him. Is all this for him just a passing fancy which amuses him, or some deep design, or the play of some force which he himself does not know? Is it his will to power, of which he speaks in his Autobiography, that is driving him from crowd to crowd. . .

Nehru for the second time in as many paragraphs is asking questions no modern politician would dare. To state it bluntly, he says the quiet part out loud. What if all the campaigning, baby kissing, handshaking, linguistic gymnastics, and public rallying is only a means to an end? What if the lines between humility and hubris are far more blurry than previously assumed?

These are questions unfathomable from Biden, Trump, or any mainstream politician in the 21st century. The will to power is brushed aside and repackaged in euphemistic language.

All the millions of dollars spent to campaign and gain public office are ‘for the sake of democracy’ or ‘for the economic livelihood of all Americans’ and so on. When in reality the sole purpose for many politicians is nothing more than a will to power.

Amidst this unreflective political class, slogans, not substance have become a means to and end. Perhaps this is why we’ve long forgotten Cincinnatus but are in no short supply of Caesars.11

Nehru, God rest his soul for having the introspection we moderns lack, presses deeper into the subversive will to power and how its purposes are served by the dilution of language. Commenting on himself he ponders:

What if the fancy turn? Men like Jawaharlal, with all their capacity for great and good work, are unsafe in democracy. . . A little twist and Jawaharlal might turn a dictator sweeping aside the paraphernalia of a slow-moving democracy. He might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism, but we all know how fascism has fattened on this language and then cast it away as useless lumber. . .His over-mastering desire to get things done, to sweep away what he dislikes and build anew, will hardly brook for long the slow processes of democracy. He may keep the husk but he will see to it that it bends to his will. In normal times he would be just an efficient and successful executive, but in this revolutionary epoch, Caesarism is always at the door, and is it not possible that Jawaharlal might fancy himself as a Caesar?

Nehru realized what neither Biden nor Trump have the circumspection to understand, namely, that beyond all the jargon and drivel about democracy a more sinister desire was and is at hand. The will to power, the insatiable desire to bend the citizen’s psyche toward a person rather than an ideal has left Caesar knocking at the gate.

Nehru knew that for India to succeed as a country he must refuse this tempting urge to bypass the democratic process for mere self-glorification and absolute power as Caesar once had. And who better to remind him of this temptation other than himself?

Nehru concludes that Indians should not vote for him for a third term in Congress because it would only aid his vanity and promote Caesarism within Congress.

He states that while he has a formidable record and will undoubtedly work hard for the Indian people, any man who views himself as indispensable must be checked.

Despite the accolades and privileges that would be allotted to Nehru if he were to continue in Congress and become the absolute leader of India, he knows he may only endeavor to do so with humility and introspection.

His final words of the essay wrap up his experiment in criticism succinctly stating:

In spite of his brave talk, Jawaharlal is obviously tired and stale and he will progressively deteriorate if he continues as President. He cannot rest, for he who rides a tiger cannot dismount. But we can at least prevent him from going astray and from mental deterioration under too heavy burdens and responsibilities. We have a right to expect good work from him in the future. Let us not spoil that and spoil him by too much adulation and praise. His conceit is already formidable. It must be checked. We want no Caesars.

Nehru went on to become the first prime minister of India and was quickly forced to remember his own admonition as the new country cascaded into intense communal violence following the partition in 1947.12

Rather than demanding subservience or usurping governmental control amidst such riots as Caesar would have undoubtedly done, Nehru could be found jumping into the middle of violent mobs in order to reason with them to choose peace over violence.

Accounts describe Nehru driving like a madman through New Delhi, stopping to disperse vicious crowds wherever they may be found. Other accounts detail over 100 refugees being invited to live on the grounds of the prime minister’s residence during the riots, many of which Nehru had saved from peril with his own hands.

Nehru had his flaws. He was accused on multiple occasions of being too friendly with the Viceroy’s wife and of sorely misunderstanding the religious tensions boiling throughout India.

However, in a world plagued by the blind pursuit of power, Nehru was all too aware of this proclivity, and actively chose not to be the Caesar of his newly-born country.

Biden, Trump, and numerous other Western political leaders would do well to learn from Mr. Nehru’s vulnerable introspection and awareness of his personal proclivity toward a will to power. And perhaps amid such reflection, they would come to see that just as in the origins of India, we the people of America want no more Caesars.

For those unfamiliar with the Gulag Archipelago and its author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, I highly recommend diving into his work. Solzhenitsyn describes from first-hand experience the horrors of Russian Gulags while grappling with the notion of evil, and good, and each individual that has the choice to act as conduit of both. Perhaps because of Cold War and Soviet paranoia our history books often skip over Russian history, especially that of the Gulags. In writing the Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn makes the cosmic battle waged within the camps impossible to miss.

While I by no means intend to veer into political ramblings, I do intend to write one more essay leading up to the election in October making the argument for why both candidates disqualify themselves due to their marred and incongruent conception of the Imago Dei.

These debates in 1858 over the politics of abolition eventually propelled Lincoln to the Republican nomination in 1860. However, what I find to be of the most interest is the format. These debates took place in 7 cities over two months. Each debate was roughly 3 hours. Yet, unlike the modern sound bite versions of debate where a self-aggrandizing moderator asks salacious questions in search of a ‘gotcha’ soundbite, the Lincoln-Douglas debate format gave the opening candidate one hour to start, his opponent had an hour and a half to reply and counter, and finally, the opener then had 30 minutes to formulate a final rebuttal. Each candidate would need to be prepared to talk about in-depth policy for upwards of one and a half hours with little prep time. This is a far cry from our current three-minute format with 30-second rebuttals.

One of the most mind-numbing components of observing modern political debates is watching a commentator ask a straightforward question and receive an answer that is so wholly unrelated that you stare dumbfounded at the television wondering if you missed something or if the English language just isn’t working anymore.

I may bite my words here in a few weeks. It has yet to be seen how much political pressure and public calls for Biden to step down from his own party will influence him. As of writing this on July 12th, 2024, he has yet to yield to increasing demands for his removal from the Democratic party. We will see how much pressure he can endure heading into the DNC.

In Trump’s defense, he has a large ego and knows it. There is no guise of humility. I am not sure what is more unsettling, a person like Trump who makes an inflated ego part of his brand or someone who is clearly thirsty for power but tries to disguise it as ‘defending democracy.’ In any case, for some comedic relief, here is a video of Trump saying nobody knows more than him about an incredibly complex topic for four minutes.

Rashtrapati is a Sanskrit word usually meaning Head of State. For those unfamiliar with Indian history, Nehru served as an instrumental leader in the Indian independence movement and was eventually the first prime minister of India.

The Modern Review was a publication widely read by the Intelligentsia of India during the struggle for independence from Britain.

The pseudonym used by Nehru was purposeful. Chanakya was an ancient Indian philosopher who is often attributed as being the Indian forerunner to Machiavelli. Chanakya is often attributed with writing the Arthashastra which a one of the first treatises on statecraft in the ancient world.

Cincinnatus was an ancient Roman statesman, who, as the legend goes, was content farming in his old age until Rome was invaded. In need of leadership, they asked him to take over full control of the state to quell the invasion. After squashing the invasion within 16 days, rather than remaining in power, he stepped down and went back to farming.

If Nehru or the story of how India became a nation interests you, I highly recommend the ‘Conflicted’ podcast. The host has a 6 part series on the partition of India. You can find the podcast on Spotify.