There are only two minutes of silence in my classroom each day. Oddly enough, it is not in the beginning. At the start of class, students are chatty. They come flying in from all four corners of the school, ready to fill their friends' imaginations with novelties from prior classes.

At times, it takes several attempts for the giddiness to subside before I can provide instructions for the day. Chatter abounds as classes progress, whether it be a lecture, Socratic discussion, or close reading. I do not mind this.

Unlike teachers of yore who ruled with a wooden ruler and demanded absolute silence, I enjoy observing students connect with literature by using the loveliest human traits: conversation.

However, I can’t help but wince at the two minutes of non-mandated silence that falls over the room at the end of the day.

As I wrap up class, I inform the students that they can grab their cell phones and prepare themselves to exit the building.

Until this injunction, their phones have been affixed in a pouch hanging on the back wall of the classroom. But in those last two minutes, as students grab those tiny black squares, an audible shift occurs.

The once mirthful classroom filled with gleeful voices quickly becomes void of all noise. The temperature of the conversation goes from that of a crowded Persian cafe to a gloomy wake on a winter day.

One by one, the students unlock their devices and instantly enter a virtual world that was all but forgotten a few moments prior.

Moments before we joked about Marc Antony’s rage in his dogs of war soliloquy, we basked in the prose of Dickens, and we marveled melodic meter of Wordsworth. In short, for the first 43 minutes of class, we collectively imagined.

But now, they stand and scroll. They snap and heart. They watch, forget, and repeat. They silence themselves. Not by force, but by choice. A modern Contrapasso1 unfolds before the final bell, and then they are gone.

At times, I, too, participate in this Contrapasso, idly checking my stocks or the score to last night’s Braves game. The little moments, historically filled with small talk or quaint reflections, have no place in this modern landscape.

There is little room for epiphany or prayer; the space for ‘goodbyes’ and ‘good days’ is becoming obsolete.

As the Poet succinctly quipped, we are ‘distracted from distraction by distraction.’2

For the better part of the last decade in both my classroom and personal life, I have struggled to clarify my often muddled thinking about humans’ relationship with new forms of media and technology. My introspection and personal practices have been far from consistent.

For seasons, I will didactically take the stance of my literary hero and proclaim ‘there is death in the camera,’3 only to binge-watch an entire season of Psyche the following month.4

A mixture of emotions, ranging from guilt to apathy, ensues each time I immerse myself in the web of useless media consumption. At times, I wonder: why do all these forms that were created for entertainment feel more like punishment?

A Medieval Idea For the Modern Age

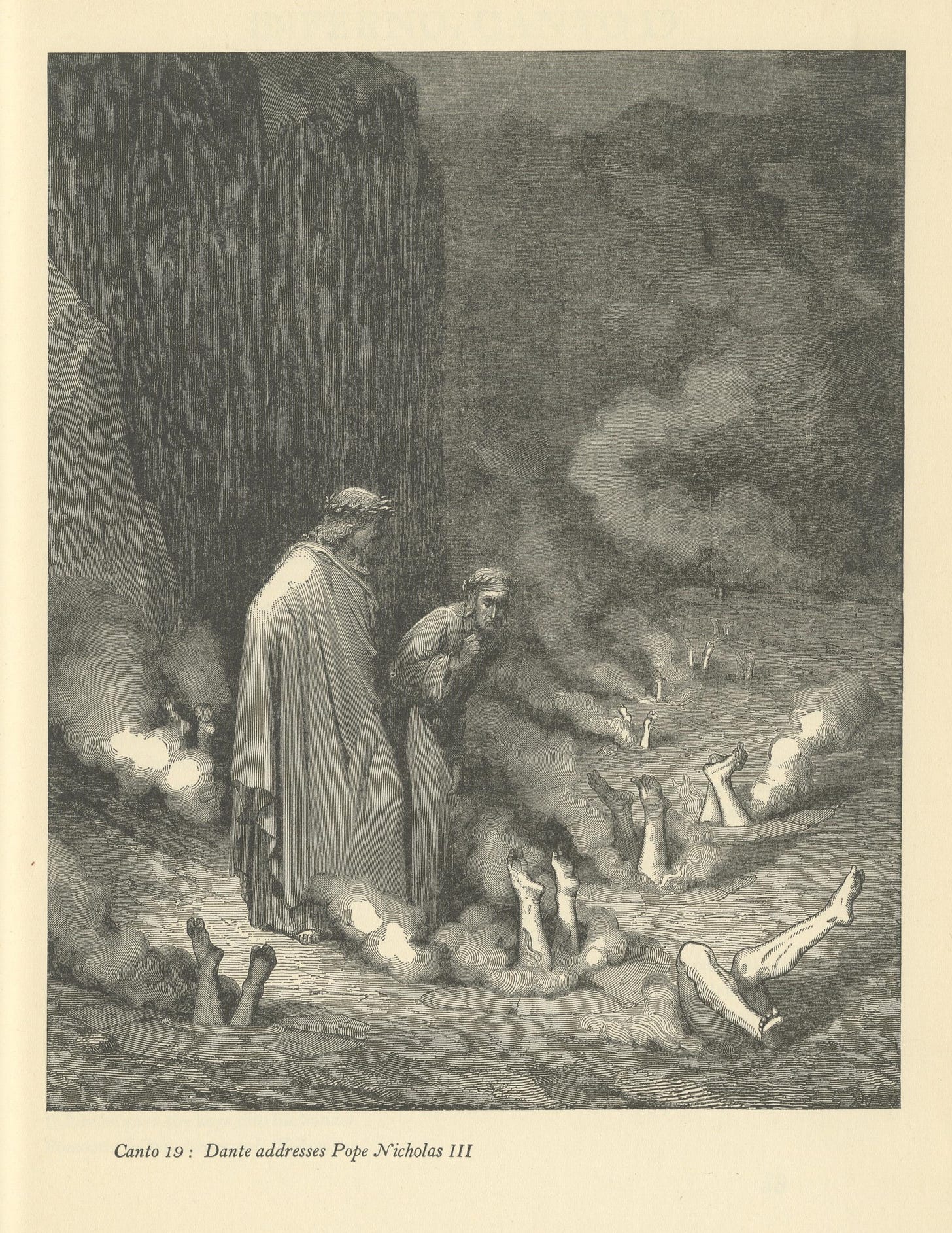

In the last two months of the spring semester, my students and I nestled ourselves down in the text of Dante’s Inferno.

While this text is regularly quoted in popular culture, most projections are vague and used in a comedic sense to place people we don’t like somewhere beyond circle seven in hell.

On the scholastic side, opinions are a bit more nuanced. For scholars of the à la carte variety, Dante’s harsh punishments and judgmental undertones are purely allegorical or in aid of artistic merit.

For scholars who believe in hell, Dante’s admonitions and insights come with the proper solemnity necessary in dealing with souls teetering on the precipice of eternity.

And while a hardy debate could ensue regarding the validity of such interpretations, as I re-read the classic, one concept rose to the fore. It is an old idea that still illuminates the modern, chronically online age. It is what Dante implements throughout the Inferno, rendered in Italian as Contrapasso.

The most literal translation means something close to ‘suffering the opposite.’

However, for Dante’s purposes in Inferno, he uses it to describe sinners in differing levels of hell who are suffering a punishment that either resembles a sin or contrasts with it according to the deeds committed by a sinner in their life on earth. In a sense, it’s an ironic form of punishment.

A few examples of this are flatterers forced to wallow in pits of human excrement because their flattering words uttered in life were full of crap, or the schismatics who are sliced into bits for sowing division amid institutions.

It is easy to recognize these Contrapasso’s throughout the Inferno, such as the account in Canto 18, when Dante writes,

This was the place we reached; the ditch beneath

held people plunged in excrement that seemed

as if it had been poured from human privies.

And while my eyes searched that abysmal sight,

I saw one with a head so smeared with feces,

one could not see if he were lay or cleric (Dante 18.112-117).5

Dante has no shortage of such punishments. From sinners chasing worthless banners around to others with their heads stuck in the ground, Dante masterfully creates Contrapassos in which sinners become in hell what they once perpetrated on earth. Their punishments match their actions.

As I contemplated this symbolic irony, I felt unsettled.

What if our modern doom-scrolling is not merely a way to kill time, but rather a slow fade into becoming what we despise? What if the mindless, forced silence and incessant checking of devices are forms of a modern Contrapasso in which we willingly participate? And what if the punishment is not simply wasted time but rather a permanently impoverished imagination wrought by the very devices which once promised to enlarge our imaginative capacity?

Deformed Imaginations

In 2019, my imagination was baptized by the works of James K.A. Smith. Through both his culturally liturgies series and the book ‘You Are What You Love,’ I began the journey of reorienting my liturgical practices on a deeper level beyond the mere intellect.

In Smith’s project, he makes the argument that humans are not merely ‘thinking-thingisms,’ but rather creatures that primarily act from the gut, subconsciously.6

The result of such observation means we are often primed to act or fall into a certain predisposition without intellectually consenting. Because of this, we are constantly being formed and deformed by external phenomena, whether or not we have the circumspection to acknowledge it. Thus, our loves can be shifted and malformed, very often without us having the slightest clue as to how or why.

We have all experienced this with the world of retail. Our mobile devices are continually bombarded with advertisements and images of items for sale. Whether it be clothes, gadgets, or services, we are primed to consume without fully understanding why we need the object we are buying. This is how we end up with an Amazon cart full of pillows shaped like turtles or impulsively drop 75 dollars on DoorDashing Taco Bell.

Ultimately, Smith’s argument boils down to you will worship or love something, even if that very thing is harmful. You are not not going to love, regardless of the consequence.

So what if, like a Dantean Contropasso, the very things we love and promised to make us feel love ultimately serve as a punishment? What if the thing promising to broaden our imagination actively constricted it instead and acted as a punishment that we are completely unaware of?

The promise fed to the world for the better part of the last two decades has been that social media and instant entertainment will enhance our connection to others and broaden our mental schema. The boundaries of time and space no longer apply. You can connect with anyone, and you can dream up anything.

But this is not the case with my students. It is not the case in the cafes crowded by masses huddled over tiny screens. It is not the case when, in the still, silent dawn of morning when the Nightingale’s song is interrupted by an Instagram notification.

I can’t help but term this development as anything other than a Contrapasso of Imagination.

As I teach Dante, I strive to incorporate Dante-inspired ideas into my classroom. We slowly comb through the portfolios of Botticelli and Doré, we marvel at the Raphaelites, and find ourselves comically confused by the likes of Bosch and Dali.7

But lately, a new image has crept into my head when reflecting on Dante. It is that of a modern Contrapasso.

I see a virtual painting of people, young and old, hovering in a pit with a hologram-like screen in front of them. The screen scrolls itself much like a YouTube short or Instagram reel. Drool hangs from the corner of expressionless lips, as the neck cranes to stare dully into the virtual abyss. Occasionally, one of the crowd will sigh and heart an image or linger on a picture. This is repeated over and over again with no end in sight.

I can’t stop thinking about this image. The irony of being punished by devices and social media that were created with the promise of connection and fulfillment is a lamentable development. And even more subtle is the fact that we think such punishment to be an enjoyable use of our time and fail to comprehend how it utterly stifles our imaginations.

Ultimately, I fear the result will eventually be the complete impotence of imagination. With the complete elimination of idle moments, when will the Still Small Voice speak to our musings? With complete absorption into the online sphere, will the subtle glances and kind words that have so often led to romance or friendship dissipate?8 What poetry will fail to be conceived by our inability to observe the beauty of the mundane?

I fear for my students. I fear for myself. I fear that we all shall suffer the opposite.

We are suffering the opposite of what this boon of technology promised us and have failed to realize it.

This is the Contropasso of imagination. We have come to love what we ought to hate and to hate what we ought to love. Lord have mercy on us.

I shall define this Italian term at length later on. Dante uses it to imply a sinner within Inferno ‘suffering the opposite’ as punishment for what he or she did in a prior life on earth.

Eliot, T S. Burnt Norton. London Faber & Faber, 1943.

I tried to hunt down a quote by C.S. Lewis where he says there is death in the camera. Whether or not he actually said it remains to be seen. I could have sworn I read it somewhere. However, the internet is littered with quotes falsely attributed to Lewis, so if anyone knows where to point me, feel free to comment.

I am not condemning the whole endeavor of watching Shawn Spencer or Burton Guster solve crime, often with great wit and candor. I do believe there are imaginative elements in sitcoms and television series. However, they make us into passive consumers rather than co-creators of meaning. They can be enjoyed, but like anything else, moderation is vital.

Alighieri, Dante . “Inferno 18 – Digital Dante.” Digitaldante.columbia.edu, digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-18/.

Smith, James K. A. You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. Grand Rapids, Michigan, Brazos Press, a Division of Baker Publishing Group, 2016.

All of these artists have created lovely, Dante-inspired art, but be careful with Bosch, his work is, in short, disturbing.

I have only touched this question in a cursory manner. However, I believe this notion to be of vital importance and plan to write on it in the future. I fear the numbing of human connection due to distraction by tech leads to many undiscovered friendships and loves. How long will these lie dormant, because in the moment they were supposed to be discovered, they were ignored?

Great work as always! I recently had a conversation with Jonathan Gold, a Buddhist scholar at Princeton who seeks to observe political theory from a Buddhist light. He was explaining how social media algorithm feeds people’s three poison (attachment, hatred, and ignorance) in order to have them stay on it longer to sell their attention to advertisers. He then connected such phenomenon to how Trump occupied public attention by inventing division and hate, therefore providing the news and media industry the attention they need. Connecting with Inferno, Buddhist also believes in different levels of hell where people suffer immensely, and it saddens me how modern technology systematically produces illusions and increase suffering, pushing people towards hell-on-earth. Really insightful observations!