Dying to Teach Clarisse in a Room Full of Mildreds

An Analysis of the American Education Systems Struggle with Attention and Literacy in a Technological Age

“With school turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word ‘intellectual’ of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamiliar.” 1

Mildred & Clarisse

Glossy eyes, dull stares, light snoring, and inattentive malaise are a few descriptors of high school students being ‘forced’ to read somewhat decent literature twice a year.2 Before I quit teaching I tried everything to get students interested in books.

I selected a wide range of books including works such as Frankenstein, A Thousand Splendid Suns, 1984, In the Time of Butterflies, and Narrative Life of Fredrick Douglas. Nothing solicited the least bit of attention. In a last-ditch effort to awaken my students to the harms of illiteracy, I decided to teach 120 freshmen Ray Bradbury’s classic dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451.

The dystopian genre often becomes hackneyed by high school English teachers parroting alarmist warnings about government overreach and societal disintegration. While Fahrenheit 451 has the potential to exacerbate such views, the similarities Bradbury projects to the future technological age are uncanny in accuracy.3

For those unfamiliar with the novel, the premise entails a firefighter named Montag being charged, along with all other firefighters, to burn books that have become illegal to own because of their contradiction to happiness and technological innovation. Montag becomes suspicious of the societal norms of incinerating literature, ultimately rebelling by reading banned books and eventually becoming a fugitive in his quest for knowledge.4

While this plot line is a bit of overkill, after all very few books are banned; the vices of the society seen in Fahrenheit 451 are beyond prescient for our current cultural moment.

A primary example of this is Montag’s wife, Mildred. Mildred is the dystopian embodiment of numerous social ills plaguing entertainment-driven societies of both past and present. She is addicted to sleeping medicine, often relying on medical professionals to pump her stomach after overdosing.5 She prefers sitting in a dark parlor room accompanied by televisions covering three entire walls with 24-hour entertainment engrossing her every moment. She continually keeps ‘seashells’ (modern-day Airpods) in her ears to tune out her husband and the outside world. She wilts under any request to think critically or deal with reality.

A counter to Mildred’s character is Clarisse. Clarisse, Montag’s 17-year-old neighbor, is full of vibrant curiosity and wonder. She is maligned by society for peculiarities such as refusing to watch television or participate in sports. Society cannot handle her inquisitiveness and keen intellect and therefore ushers her to the margins.

In a dialogue between Montag and Clarisse, the reader gets a clear view of how Clarisse struggles to fit the mold of an entertainment-driven society. The conversation is quoted at length below:

“He felt at ease and comfortable. "Why aren't you in school? I see you every day wandering around” (Montag). "Oh, they don't miss me," she said (Clarisse). "I'm anti-social, they say. I don't mix. It's so strange. I'm very social indeed. It all depends on what you mean by social, doesn't it? Social to me means talking about things like this." She rattled some chestnuts that had fallen off the tree in the front yard. "Or talking about how strange the world is. Being with people is nice. But I don't think it's social to get a bunch of people together and then not let them talk, do you? An hour of TV class, an hour of basketball or baseball or running, another hour of transcription history or painting pictures, and more sports, but do you know, we never ask questions, or at least most don't; they just run the answers at you, bing, bing, bing, and us sitting there for four more hours of film teacher. That's not social to me at all.”

The irony of reading a passage of this sort while teaching in a school full of students and staff completely consumed by technology and entertainment is a surreal experience.6 Our society wants students to turn out like Clariesse, yet fills them with gadgets, toys, devices, and instructions leading them straight to Mildred’s manners.

Schools and parents alike would love for students to learn social skills akin to Clarisse, yet endeavor to do so by handing them tablets, laptops, and headphones. Smart, well-meaning administrations and school boards push for social-emotional learning while constantly undercutting themselves by creating curricula and by using technology proven to be antithetical to the proper ingredients for socialization.

When the cords are cut, or the power goes out and the only medium for communicating is direct person-to-person, only then can students return to the essence of what true social-emotional learning entails. Copious amounts of resources and time are spent to craft more ‘efficient’ and ‘effective’ learning technologies without pausing to reflect on the damage caused by the mediums being used.

The Cost of Technocratic Classrooms

An example of this is the post-COVID push for each student to have their own classroom Chromebook. In theory, it sounds practical for each student to have a device to read or write upon that is not dependent on a physical classroom location. However, the secondary repercussions of such mandates have been disastrous.

Even with the pandemic subsiding, because schools spent significant money on computers, a push continues to be made by many administrators to persist in the use of Chromebooks for everyday instruction. In fact, the last school I taught at required students to bring their computers to class each day and for teachers to assign all work via Google Classroom.7 No more paper materials or inefficient dissemination of information, correct?

This was far from the case. Students used these computers in class to watch Hulu, YouTube, Netflix, and TikTok, text friends, online shop, and play video games. While the majority of these websites were technically blocked, a few tech-savvy students would hack around the blockers and gladly help other students do the same.

The results of this are detrimental in the classroom. The struggle to keep students off of personal phones is already a difficult task, so sourcing and mandating them to use an extension of their phone in the form of a computer is only an exacerbation of the attention gap already pre-existing in the majority of school-aged students.

The results are schools filled with Mildred-esque students.8 Seashells or headphones slip into their ears whenever possible, and phone, or computer screens filled with meaningless babble are constantly vying for every second of attention. General apathy toward all constructive learning endeavors is the norm. Clarisse, with all her luminous curiosity, is seldom to be found.

Concerns of this sort ought to prompt educators to perform an autopsy of current educational trends. Additionally, educators must learn to identify if the promises of unhindered technological advances are actually beneficial for students.

The Attention Gap

A few of the more glaring and obvious results of such blind adherence to modern technologies are clearly the attention gap and rising illiteracy rates across American schools. The term attention gap, as I am using it, refers to the dwindling ability of the American populace to pay close attention to any subject for an elongated period of time.

The poet Mary Oliver, writing in her work Upstream said, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”9 Unfortunately, the modern age is riddled with attention deficits. Devoted attention is now a rarity.

In a somewhat strange and often quoted study humans are now thought to have attention spans hovering right around 8 seconds, or to put it bluntly, attention spans one second less than a goldfish. While this study is far from able to withstand scientific scrutiny, ( although this didn’t stop publications like Time Magazine and New York Times from jumping all over it)10 the sentiment holds true that in an increasingly digitized age, the influx of information competing for our attention is immense.

A study on the incidents of ADHD in adolescents from 2003 to 2011 found a 42% increase in the prevalence of ADHD for children between the ages of 4 and 17.11 This statistic, nearly a decade old, is only one indicator of the persistent attention draught sweeping through American students.

In the fraught culture wars of the twenty-first century, a heated debate is often found at school board meetings and libraries about censorship and whether or not certain books should be banned outright. Loud voices on both sides fight tooth and nail to either remove or keep debatable books on the shelves of school libraries. And while this discussion has some merit along the lines of 1st Amendment issues, the irony is that books don’t have to be banned anymore for students not to read them, the inattentive self is already omitting the desire to read altogether in many students.

The inability to educate students to a baseline of attention has led to literary impotence. Few students have the attentive faculties to complete an entire work of fiction. This has created an education system far more akin to A Brave New World or F451 rather than an Orwellian 1984.

Neil Postman pointed to this clearly in his seminal work Amusing Ourselves to Death.12 Society need not be up in arms claiming school boards or government bureaucrats are acting Orwellian in their control over reading materials, when in fact the students are unlikely to have the attention span to read such banned books in the first place. The real concern for educators and parents alike is that A Brave New World-type scenario will dominate the future. This occurs when a society has forgotten all history and works of art out of mere apathy. Consequently, entertainment culture, not government overreach, is a far more pressing discussion for the modern person concerned with educational policy.

The Emergence of Illiteracy

It should come as no surprise that lagging only a step or two behind the attention gap is a rising rate of illiteracy. Bradbury was concerned about the phenomena of illiteracy in the West as early as the 1950s. Personally, as a high school teacher in the year 2022 trying to teach 12th graders with reading levels varying around 3rd or 4th grade, I understand the sentiment.

The rate of illiterate or semi-literate individuals living within the United States is perhaps the most regrettable indictment of the American educational system to date. A conglomeration of studies compiled from The Literacy Project, The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies showed that over half the American population cannot read a book written on an 8th-grade level or above.13

An objection could be raised on the grounds that the United States has numerous refugees and immigrants who are non-native English speakers. However, non-native English speakers only account for 22 percent of the population according to the census.14 Not to mention a good number of immigrants obtain a high level of English literacy outstripping that of their native English-speaking counterparts.

Whatever excuses try to account for this unsettling trend in America does little to assuage the concerns of growing illiteracy amidst our current educational system. Such grim findings have educators, parents, and students all questioning the modern presumption, often utopian in thinking, that the march forward of modern technology and social media platforms will somehow bring a newfound boon of educational progress to future generations.

We have far more technological resources and access to information than all the previous generations combined, yet literacy is still on the decline. More children now have access to education, but this access does not correlate with positive literary outcomes.

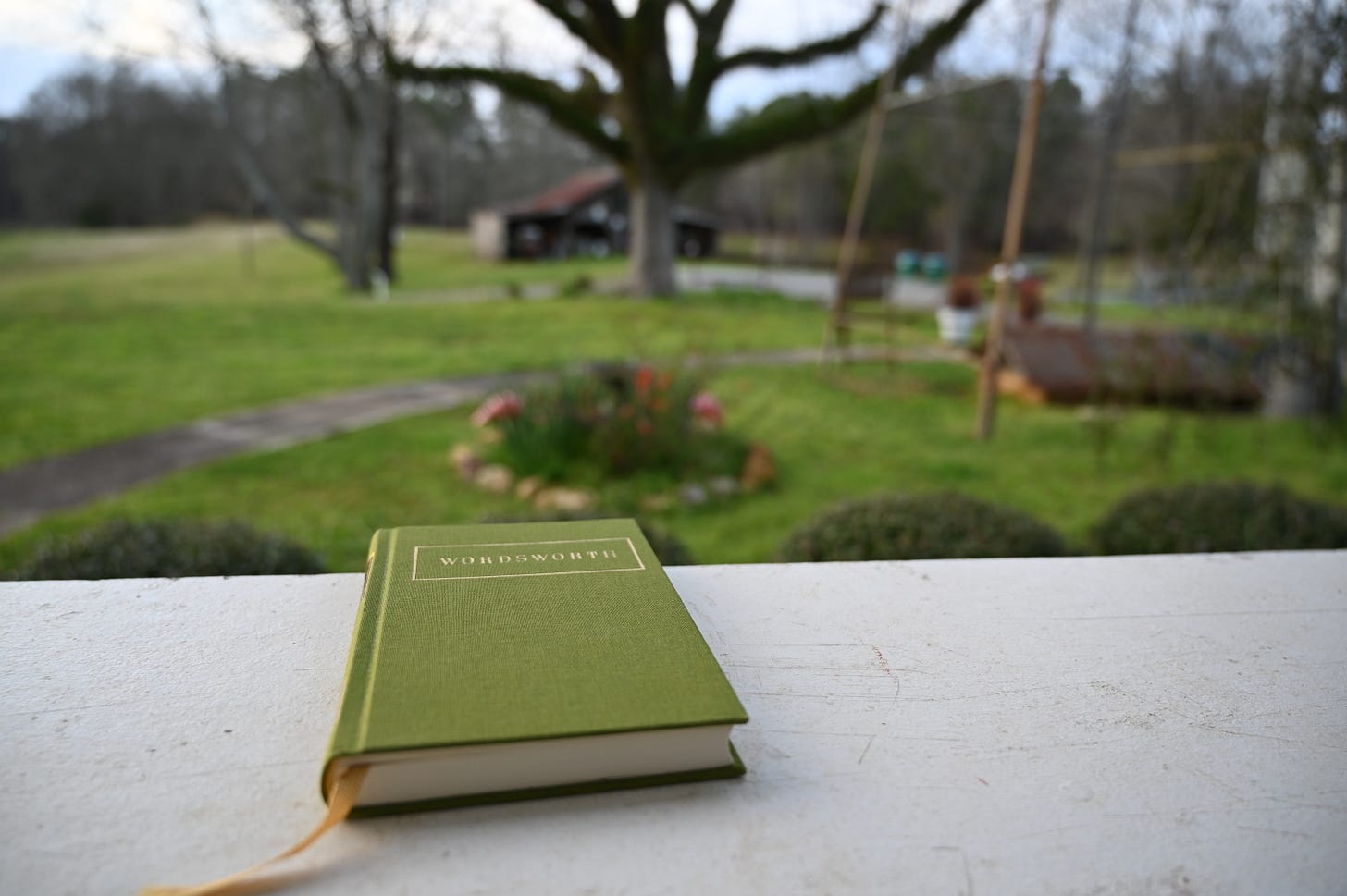

The question of what culture shall lose if literacy wanes in the tides of entertainment-based culture must be posed. What will occur to an entire country unable to enjoy the lovely prose of Austen or the lyrical brilliance of Wordsworth? Will the ability to perceive beauty in the literary realm cease from existence if students can no longer handle a complex text? What will become of our shared consciousness if we cannot consult Dostoevsky for suffering or Dante for sublime imagery?

This loss of literacy comes at a great price. Not only will the prevailing winds of a semi-literate culture cause the loss of shared history and literary enjoyment, but the things that are beautiful, lofty, and true shall be diminished. A key theme of this journal revolves around the concept of mimesis, which is the concept of creating art in such a way that it imitates the real world. The real world is filled to the brim with beauty and pain, joy and sorrow, and numerous other deep emotions often captured in the art we create.

If the world we inhabit becomes plastic, artificial, and distracted what art shall our future generations inherit? While such musings will likely be written off as fictionalized nostalgia for an age long past and unrealistic in nature, I challenge the reader, with circumspection proper, to sit face-to-face with the realities brought about by an inattentive and illiterate society, bent on progress and entertainment at all cost. Soon you, dear reader will likely find yourself in a sea full of Mildreds begging for anyone to be like Clarisse.

*Note from the author*

The essay above is the first installment of my weekly essays to be discoursed in ‘The Mimetic Journal.’ I have offered a 30,000-foot view of ideas I have been mulling on for years. I plan to use less of a broad brush to paint with in future essays and to offer more detailed solutions and critiques. For now, I ask for patience and forbearance for areas of work I have treated unfairly. I hope to refine my writing in the weeks and years to come.

Please feel free to share this essay with those who are interested and feel free to offer feedback or comments. Additionally, if you missed my introduction to the journal you can find my overview essay embedded here.

Tune in next week for my next essay titled ‘Artificial Intelligence and the Upheaval of Collective Beauty.’

Kindly,

T.S.

Bradbury, R. (2013) in Fahrenheit 451. New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 55.

In my writing, I will often implement footnotes to reference other books or in a style similar to David Foster Wallace as an avenue for side tangents and additional information excluded from the body of the text. Feel free to ignore such rambles if the diatribes do not suit your fancy. for this particular footnote, I found it of some interest to mention that most private schools and public schools only require students to read one to two full works of literature per year. Keep in mind students spend on average 180 days a year in their English composition courses. These classes range anywhere between 50 and 90 minutes. Not to mention, many of the books selected for reading are deficient in complexity. An interesting experiment here is to compare a public school reading list in 1922 to modern-day lists. In 1922 9th graders were encouraged to read complex text, usually on an 11th to 12th-grade level, while now we are barely encouraging novels for 9th graders written on a 5th-grade level. Link here.

F451 was written in 1953 amidst the twilight of WWII and nuclear paranoia. However, Bradbury’s most insightful predictions involve the repercussions of an increasingly plastic society shaped by entertainment and materialism. It is easy for teachers to outline the parallels between authoritarian leaders, nuclear politics, and global geopolitics while missing the entire motif of superficiality brought about by the entertainment and marketing industry.

In a strange sort of ending Montag ends up on the outskirts of town amidst a homeless colony of ex-professors, authors, linguists, and philosophers. This group of exiles memorize large portions of text in an act of resistance to a society insistent on devaluing history and forgetting the importance of literacy. One cannot help but draw similarities to modern ‘societal exiles’ in the current political climate. Cancel culture tends to push certain unpopular scholars or academics to the fringes for often simply holding orthodox views.

Overdose or substance abuse is a common motif both in F451 with addiction to sleeping pills being a major factor and in Brave New World where the populace is addicted to Soma pills. The basic line of thinking is as people become less inclined to reflection, beauty, responsibility, and shared meaning people have to resort to alternative methods of coping with reality. The unsettling reality provided by such predictions is now well on its way to becoming a real life. A simple glance at the CDC’s number of recorded overdoses in the past 20 years is cause for grave concern. From 2001 to 2021 the incidents of overdose deaths per 100,000 people in the United States rose from 6.8 to 32.4.

I include myself in this category at times. I would like to be untainted by entertainment culture as a whole, however, I often find myself being sucked into the fray.

Often students would come to class without chargers and a dead Chromebook. This automatically excludes the participation of that student. Penalties for such unprepared students were only minor leading to a trend of students intentionally forgetting chargers, being unable to participate, and therefore causing classroom disruptions for the entirety of class.

It is worth noting I am painting a broad brush here. Not every student is plagued by attention deficits. I speak broadly from my experience as a teacher. The ratio I observed personally for every 10 or so students that had poor attention spans 1 student would be focused and dedicated. Perhaps this is a form of the Pareto Principle in motion at an early age.

Oliver, M. (2016). Upstream : select essays. New York: Penguin Press.

If you search the internet you will find all kinds of marketing propaganda utilizing the goldfish principle. The problem is that attention is incredibly difficult to quantify as this article describes.

Maybe even more concerning than the increased incidents of ADHD are the prescription drugs widely used to medicate adolescents with ADHD. The over-medicating of America’s youth continues to stunt the growth of bright, energetic students by feeding them ‘downers’ that radically alter their moods and personalities. Evidence for this trend is documented here according to the CDC.

Postman, N. (2007). Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Showbusiness. London: Methuen.

The importance of Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death cannot be understated. This work gives a broad analysis of the rise of entertainment culture, looking closely at historical, cultural, and technological shifts that have led us into the modern, plastic society.

"I will not walk with your progressive apes,

erect and sapient. Before them gapes

the dark abyss to which their progress tends -

if by God's mercy progress ever ends,

and does not ceaselessly revolve the same

unfruitful course with changing of a name..." - Tolkien, Mythopoeia

Great work, Seth!

Well done! Looking forward to further ruminations on the path forward. I suspect that, in the end, it will have more to do with the cultivation of virtue in the midst of rapid technological advance than a retreat from it. Jason Thacker has been writing along the lines of developing a Christian ethic in a technological age etc. I hope to read through some of his stuff when I get some bandwidth.